Three articles written by Janaki Patrik have been published in NARTANAM Journal.

Founder Publisher: G M Sarma, Kuchipudi Kala Kendra, Mumbai

Founder Editor: M. Nagabhushana Sarma

Chief Editor: Madhavi Puranam

Published by: Sahrdaya Arts Trust, Hyderabad

NARTANAM, A Quarterly Journal of Indian Dance, Volume XI, No. 3, July – September, 2011, Hyderabad, India

Indian dance scholar Dr. Sunil Kothari suggested my name to NARTANAM’s Editor-in-Chief Madhavi Puranam, when she decided to survey Kathak beyond the borders of its Indian homeland. I declined twice, principally because the subject is so vast and I am still an active dancer, teacher and choreographer. However, Dr. Kothari and Editor-in-Chief Puranam persisted, and I was eventually enticed by the thought that “we have to start somewhere”.

AMERICAN TRIUMVIRATE: Presenting Indian Arts in the United States:

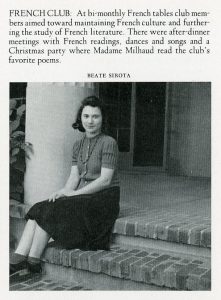

Beate Sirota Gordon @ Asia Society – Alan Pally @ The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts – Robert & Helene Browning @ World Music Institute

NARTANAM, A Quarterly Journal of Indian Dance, Volume XIV, No. 1, January – March, 2014, Hyderabad, India. Revised and expanded, 18 February 2022.

The passing of Beate Sirota Gordon on 30 December 2012 shocked me with the finality of the loss – a legend, whose work had touched me deeply, but about whom I knew so little. Mrs. Gordon’s death prompted me to think about Asia Society and two other major New York City cultural institutions, whose resources and programming continue to instruct and inspire me – the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts and World Music Institute. The artistic and programming directors of these three institutions played leading roles in American cultural life during the latter decades of the 20th Century and opening decade of the 21st Century. The work of Beate Sirota Gordon at Asia Society, Alan Pally at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and Robert and Helene Browning at World Music Institute fueled a crucial shift in cultural programming, reorienting it from a predominantly Euro-centric focus to a global perspective.

Fourteen years into the 21st Century, it is evident that these presenters were ahead of their times in showcasing the rich cultural diversity of the world community, setting the course for programming in three major and highly-visible American institutions. Of particular interest is the contrast of policies and funding as implemented in three different institutional paradigms – a large, privately-founded and privately-funded arts and education organization, a programming department within New York City’s public library system, and an individually-founded organization focused exclusively on presenting world music and dance.

PART I

Asia Society, The New York Public Library of the Performing Arts and World Music Institute appear frequently in the itineraries of India’s eminent artists. This article gives NARTANAM readers a perspective on these major institutions, and on the programming directors who have shaped their curatorial decisions. Moreover, events during the forty years encompassing the artistic directorships of Beate Gordon, Alan Pally and the Brownings provide examples of the seismic shifts in promotion, funding and information technology during the latter 20th and early 21st Centuries. Details from the lives and work of these individuals also show the important role of American philanthropy, entrepreneurial ingenuity and individual initiative in presenting the performing arts.

This article does not focus exclusively on Indian dance and its inextricable companion, music. The work of all three organizations profiled represents the ethnic make-up of the diverse population of New York City and of the United States. However, programming of Indian arts has played a central role in the work of all three directorships, and examples of their work in this area are given wherever possible.

Beate Sirota Gordon – Asia Society

A Tribute

Asia Society was organized by American philanthropist John D. Rockefeller III in 1956. Following his college graduation in 1929, he made a world tour, ending in Japan. This visit, plus his service there at the end of World War II, fostered his lifelong interest in Japan and all of Asia. The idealism and sense of public service guiding Rockefeller’s life is reflected in Asia Society’s current Mission Statement: “Asia Society is the leading educational organization dedicated to promoting mutual understanding and strengthening partnerships among peoples, leaders and institutions of Asia and the United States in a global context.”

Beate Sirota Gordon did not set out to make a career in arts management, which culminated in her position as Director of the Performances, Films and Lectures at Asia Society. Many of the pivotal events early in her career occurred when Ms. Gordon seized opportunities as they serendipitously presented themselves, while keeping in mind a practical need to support herself financially. But once set on the path of presenting Asian performing arts through programming at Japan Society and Asia Society , Ms. Sirota-Gordon concentrated her linguistic talents, management skills and refined aesthetic judgment to fulfilling her vision to the utmost.

Early Years – Childhood in Japan, Education at Mills College, Supporting Herself During World War II

Daughter of renowned Russian-Austrian pianist Leo Sirota, Beate was 5 ½ years old (1929) when she and her mother Augustine Horenstein Sirota moved from Vienna to Japan to join her father, who had been appointed professor of music at the Imperial Academy of Music in Tokyo. [1]

From The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Volume 11 | Issue 2 | Article ID 3886 | Jan 21, 2013

Though her sense of artistic excellence was nurtured in a household filled with music, Beate did not choose to become a professional performing artist. She decided instead to concentrate on languages in her college undergraduate studies. When she moved to Oakland, California in 1939 to attend Mills College, she was already fluent in German, Japanese, English, Russian and French.

Japan’s attack on America’s naval base at Pearl Harbor (7 December 1941) abruptly changed Beate Sirota’s life. Living in the United States, which immediately declared war on Japan, she was cut off from financial support and communication with her parents, who remained in Japan. As her savings dwindled, Ms. Sirota realized that she needed to find paid work. Consequently she arranged for an extension of her summer job translating Japanese broadcasts for the Office of War Information in the Foreign Broadcast Information Service. With permission from the Mills College administration, Beate Sirota fulfilled her graduation requirements by writing term papers and sitting for exams rather than attending classes and residing on campus.

During her last two years as an off-campus student at Mills College, Beate Sirota lived a highly disciplined and compartmentalized life, devoting her mornings to independent college studies and the rest of the day until 11pm to translating broadcasts arriving in California from Japan. She qualified for this job not by taking an examination, but by a dramatic incident – her discovery of the approach of a Japanese submarine into San Francisco harbor. Her careful translation work and sensitive ear to colloquial Japanese picked up information which had been overlooked by the American listening post in Portland, Oregon. Ms. Sirota was also responsible for writing the script and choosing music for daily broadcasts to Japan, delivering America’s answer to Japanese propaganda broadcasts aimed at American troops by “Tokyo Rose”. [2] In her book “The Only Woman in the Room”, Beate Sirota Gordon writes that “as a direct consequence of the war, I found myself largely self-reliant by the age of nineteen.” [3]

Examining the lives of people like Beate Sirota Gordon, who have so profoundly contributed to our perceptions and knowledge of a multi-cultural world, we may ask what factors shaped their inclusive world view. Beate Sirota was hardly twenty years old when she had already applied for United States citizenship. Though she still felt a great admiration for Japanese culture and a loyalty to her Japanese friends, she held the Japanese government responsible for its attack on America. Putting a personal face on a nation considered en masse to be “the enemy” may have helped Beate Sirota to sort through such seemingly contradictory loyalties, and to find ways to contribute toward a peaceful world community in her subsequent career.

To Japan in Search of Her Parents, Working for the United States Foreign Economic Administration

With no news about her parents during the war years, Beate desperately wanted to return to Japan to find them. After Japan’s surrender on 15 August 1945 she started looking for work which would take her to Japan. Because of her Japanese language skills and work for the Office of War Information, Ms. Sirota was hired by the Foreign Economic Administration to participate in organizing the Japanese Occupation under General Douglas MacArthur. She arrived in Tokyo on Christmas Eve 1945, the only civilian American woman in Japan. Though she had received her United States citizenship in January 1945, Beate Sirota Gordon wrote in her autobiography, “after a five-year absence, I came home” [4] – home to her parents and to the country where she had lived during the ten formative years of her childhood.

Searching for her parents, Beate Sirota went to the street where she had lived in Tokyo as a child. “There were a few buildings left standing, but I could see no private homes. Everything I remembered had vanished…our house was not where my feet told me it should be. What I was looking at were merely traces of it, the square foundation stones.” [5] Driving through similar streets, she finally recognized the home of a German singer, her parents’ friend, who suggested that her parents might have been put under house arrest in Karuizawa, a mountain village outside Tokyo, where the Sirotas, like many foreigners, had a summer home.

In her first leave from official work, Ms. Sirota went to Karuizawa and found her parents – living but in acute need of food and medical attention. The summer cottages had no heating or insulation, and the winter cold and inadequate food supply had taken their toll. Beate Sirota’s mother was lying in bed – cold, bloated from malnutrition and too weak to stand. Moving her parents back to Tokyo, Ms. Gordon set about foraging for food and medical care for them.

When she had returned to Japan in 1945, Beate Sirota found a very different country from the one she left as an almost-sixteen year old in 1939. Moreover, Ms. Sirota herself had changed, becoming a mature woman with clearly defined ideas about women and society. Her mother’s example of active participation during her childhood in male-dominated Japanese society, was reinforced by the ideals of the all-women’s Mills College, whose President from 1916 to 1943 was the progressive educator, social and peace activist Aurelia Reinhardt. Empowered by this philosophy and by her success at supporting herself in wartime America – mainly in professions considered appropriate for men only – Ms. Sirota had developed distinct ideas about women’s capabilities and rights.

Writing Women into the Post-War Japanese Constitution

Initially hired as an interpreter for General MacArthur’s staff, during America’s post WW II occupation of Japan, Beate Sirota soon became a member of the committee assigned the task of drafting a new, post-war Japanese Constitution. In early 1946, the Japanese government had submitted two drafts for a new constitution to the General Headquarters of the Allied forces, but they were both rejected as being too conservative. General MacArthur, Chief of the Allied Forces, ordered his staff to draft their own version in one week.

Beate Sirota’s serendipitous assignment as the only woman in the subcommittee on civil rights ensured that Japan’s postwar constitution protected equality between men and women, at work and in the home. The section on women’s rights fell to Beate with the almost flippant words of her supervisor: “You’re a woman; why don’t you write the women’s rights section?”

In childhood while playing in the homes of her Japanese friends, Beate had closely observed the subservient position of women. Her knowledge of the Japanese language, as well as her progressive ideas about women’s capabilities and her intimate knowledge of Japanese cultural mores, informed her draft. The wording of Beate’s draft prompted Lt. Col. Charles L. Kades, head of the constitutional steering committee, to say to Ms. Gordon, “My God, you have given Japanese women more rights than in the American Constitution.” In her memoire The Only Woman in the Room, Ms. Gordon recalls answering him, “Colonel Kades, that’s not very difficult to do, because women are not in the American Constitution.” [6]

The importance of Beate Sirota’s contribution to the Japanese Constitution is attested by the following quotes from that Constitution:

“All of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status or family origin.” Article 14, The Japanese Constitution

“Marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes and it shall be maintained through mutual cooperation with the equal rights of husband and wife as a basis. With regard to choice of spouse, property rights, inheritance, choice of domicile, divorce and other matters pertaining to marriage and the family, laws shall be enacted from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes.” Article 24, The Japanese Constitution

Inclusion of principles of equal rights was a directive from General Douglas MacArthur, and the constitution would likely not have been approved without the inclusion of articles on civil rights. However, Article 24, which included a statement about “the essential equality of the sexes”, was a marked departure even from the American constitution. Nevertheless, Ms. Gordan insisted that a democratic constitution in the twentieth century must include a statement on women’s rights, and she wore down the original disinterest of the middle aged American lawyers who dominated the constitution drafting team. These men were not opposed in principle to women’s rights. However, they did not believe that questions of marriage, divorce, property, inheritance, and family — framed in violation of basic principles and traditions of Japanese culture, and absent from the American constitution — belonged in a Japanese constitution.

When Article 24 was initially presented to the Japanese, they strenuously objected, “This doesn’t fit our culture, doesn’t fit our history; it doesn’t fit our way of life”. But during the previous fourteen hours of debates, Beate had won the gratitude of the Japanese leaders for backing them in various disagreements with the Americans. Consequently, when Lt. Col. Charles L. Kades said, “Miss Sirota has her heart set on the women’s rights [sections]. Why don’t we pass them?”, the Japanese delegation capitulated. In the absence of Beata’s pressure, women’s rights, including the ‘equality of the sexes’, would not have appeared in the MacArthur constitution.

Decades of Silence

The Japanese government promulgated the constitution on November 3, 1946. It took effect on May 3, 1947, granting universal suffrage, stripping Emperor Hirohito of all but symbolic power, stipulating a bill of rights, abolishing peerage, and outlawing Japan’s right to make war. To gain acceptance from the Japanese public, American involvement was kept secret until 1971.

“Because her work was secret, Ms. Gordon said nothing about her role in postwar Japan. She later remained silent because she did not want her youth—and the fact that she was an American—to become ammunition for the Japanese conservatives who have long clamored for constitutional revision. It was not until the mid-1980s, when the clauses came under attack by Japanese conservatives, that Beate began to speak out about it publicly and ardently. [7]

Her memoir, published in Japanese in 1995 as Christmas 1945: The Biography of the Woman Who Wrote the Equal Rights Clause of the Japanese Constitution, and in English two years later as The Only Woman in the Room, made her a celebrity in Japan. She lectured widely, appeared on television and was the subject of the stage play, A String of Pearls, by James Miki, and a documentary film The Gift from Beate”, screenplay and direction by Tomoko Fujiwara, released in April 2005.

First Steps as a Presenter and Promoter of Asian Performing Arts – Japan Society

Soon after returning from Japan, Beate Sirota married American–born Lt. Joseph Gordon, another Japanese-language expert with whom she had worked in Tokyo on the draft of the Japanese constitution. The birth of two children did not deter Beate Sirota Gordon from working professionally. From an unassuming job in 1952 as translator for visiting Japanese feminist Fusae Ichikawa, …..

…..Ms. Gordon went on to part-time work at Japan Society in 1954 as Director of Student Programs, providing career and job counseling to Japanese students in New York. Performing arts were never far from Beate Gordon’s mind. Finding a talented violin student washing dishes to earn money, Ms. Gordon devised a means to augment her advisees’ financial resources. “With the help of a small endowment and a title – Director of the Performing Arts Program – I put together teams of young performers who went around to various schools presenting dance and music programs….” [8]

Beate Gordon’s early steps in arts presentation served a dual purpose, providing performance opportunities and income to Japanese student and professional artists, while simultaneously increasing awareness in America of Japanese culture. Immediately following World War II many Americans regarded Japan “as a defeated country and its people as cultural inferiors, if not enemies”. [9] Addressing the need to educate Americans about the country of her childhood, Ms. Gordon directed her ingenuity and perseverance to promoting Japanese arts, leading to her appointment in 1958 as Director of Performing Arts at Japan Society.

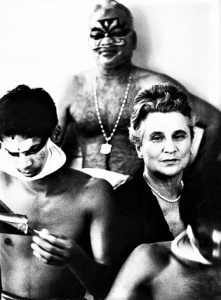

Director of the Performing Arts Program at Asia Society

When she became Director of the Performing Arts Program at Asia Society in 1970, Beate Gordon expanded this pattern, now arranging performances in New York City schools by eminent artists from all Asian traditions represented in the New York City population, including performances and lecture-demonstrations by Indian dancer Indrani Rehman. Moreover, with the arena of her activities vastly expanded in her roles at Asia Society, Ms. Gordon spent the next over-23 years until her retirement in 1993 traveling to the most central as well as the most remote areas of Asia, finding great artists and performance traditions and showcasing them in the United States.

Spanning six decades from 1954 until her death in 2012, Beate Gordon’s career in presenting Asian performing arts featured some of India’s greatest artists. Asia Society’s tours to universities and cultural organizations in major American cities frequently began in New York City’s Carnegie Hall. Its 2800-seat capacity presents a daunting challenge to every impresario, but Beate Gordon always managed to draw a respectable audience, and sometimes an overflow crowd.

When Asia Society decided to build its own home on Park Avenue and 70th Street in Manhattan, Mrs. Gordon contributed significantly to the design of its 258-seat Lila Acheson Wallace Auditorium. One of New York City’s most elegant theaters, its intimate and warm atmosphere is eminently suited for presenting Asian performing arts, whose delicate musical timbres, subtle facial expressions and intricate gesture language would easily be lost in larger theaters. The extensive roster of famous South Asian artists and troupes presented by Mrs. Gordon at both super-sized Carnegie Hall and intimate Asia Society includes Indian troupes and artists Pandit Birju Maharaj, the late Shrimati Sanjukta Panigrahi, Peruliai Chhau, the late Indrani Rehman and Sri Lankan dancers and musicians. Beate Gordon’s appreciation of Indian performing arts is evident in her choice of Kathakali artists from Kerala Kalamandalam to present the inaugural performance on Asia Society’s new stage on Friday, 24 April 1981. Like so many performances arranged by Ms. Gordon before and after, this one was reviewed by the New York Times’ renowned dance critic Anna Kisselgoff, A dance scholar of Russian heritage, Ms. Kisselgoff’s reviews of non-Western dance were eloquently descriptive and sympathetic to aesthetics not necessarily familiar to the newspaper’s readership.

Ms. Gordon exhibited extraordinary promotional acumen – not only insuring that knowledgeable writers and media would attend Asia Society performances, but also bringing seemingly unrelated people together in mutually beneficial partnerships. Acutely aware of the budgetary constraints mandated by Asia Society’s multi-faceted mission, Beate Gordon always managed to find the resources necessary for presenting world-class artists from Asia and connecting them with their compatriots, who could give familiar comfort to the visiting artists. She attributed her social and management skills to observing her mother entertain artists and art connoisseurs with good food and sparkling conversation in her family’s Viennese and Tokyo homes. Treating art as a human need, much like food and social interchange, and not like a business, she found ways to achieve her goals without excessive expenditures.

An extended quote from her memoir summarizes Beate Gordon’s working philosophy: “In the fifties and sixties…. Asian culture in general was ‘exotic’. Only a handful of scholars understood its richness and variety…From 1970 on…I put all my efforts into trying to communicate the essence of Asian culture to Americans through first-rate, purely traditional art forms. To this end I spent from four to six weeks every year in Asia, researching the old arts and negotiating with the performers, before bringing them to the States.” [10] The result of Mrs. Gordon’s tireless efforts was, in the words of her son Geoffrey Gordon at Asia Society’s 28 April 2013 memorial tribute, “to make the indigenous international”.

At least as early as 1974 Ms. Gordon took visiting Asian troupes to the sound stage at Brooklyn College TV Center, and with the Center’s director Harvey Ganot, she produced video documentaries. Reproduced as videotapes of sufficient quality for network broadcast, educational purposes and private purchase, the videos recorded Asia Society’s early US tours of some of the greatest artists and troupes from Asia, including Pt. Birju Maharaj, Smt. Sitara Devi and Perulia Chhau. Watching Ms. Gordon working in the studio, delivering live, on-camera narration and simultaneously directing split-second dissolves from one camera to another, one witnessed skills honed while Beate was still in her late teens and working for the United State’s Office of War Information. [11]

Giving a perspective to Beate Gordon’s pioneering documentation work for Asia Society in the 1970’s, one may note that these videos preceded later work in this genre: Dance in America debuted on PBS in 1976; Eye on Dance was launched in 1981; and Lincoln Center’s Dance on Camera Festival was first presented in 1998. The quality and enduring value of Beate Gordon’s early Asian dance performance documentaries is evident from their inclusion in the Dance Collection of the NY Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Though Beate Gordon retired from the directorship of performing arts at Asia Society in 1993, she continued cultural activities as consultant and writer until her death in 2012. She was a woman of modest stature, but one never looked past or down at her. She had a commanding presence and a decisive managerial style. At Beate Gordon’s retirement party, the Japanese Butoh artist Kazuo Ohno danced to the accompaniment of Frank Sinatra’s famous song “My Way”. The lyrics, as knowing laughter from her friends and colleagues attested, might have been spoken by Beate Gordon herself. “I’ve lived a life that’s full. I’ve traveled each and ev’ry highway: But more, much more than this, I did it my way.” [12]

[1] From The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 2, 21 January 2013. Obituary written by Roger Pulvers with a note by Milton Esman. “I left Vienna when I was 5 ½ years old, and the culture shock I received upon arrival at the Kobe [Tokyo] docks was such that it erased all memory of Vienna. I had never seen an Asian before, and the sight of all those Japanese men and women, black-haired and black-eyed, with a different color of skin than mine, caused me to ask my mother whether they were all brothers and sisters. My mother, shocked by this question, became motivated to integrate me into Japanese society.” It didn’t take her long to assimilate. “I played with our neighbors’ children, visited their homes, learned Japanese games, watched them do homework and practice the koto and the piano, as well as their lessons in flower arrangement and Japanese dance.”

[2] The Only Woman in the Room, A Memoir by Beate Sirota Gordon. Kodansha International, Tokyo-New York-London, 1st edition 1997 p. 88

“After graduation [from Mills College] I transferred to the Office of War Information … My job was to produce broadcasts targeted at the Japanese and designed to simultaneously inform and demoralize – San Francisco’s answer to the broadcasts of Tokyo Rose, the voice of Japanese propaganda for front-line U.S. Troops. The short broadcasts I produced consisted of three minutes of music accompanied by a seven-minute message. I selected the music and wrote the scripts …. I wrote hundreds of shows.”

[6] Jewish Women’s Archive. “Birth of Beate Sirota Gordon, who wrote equality into the postwar Japanese constitution.” (Viewed on January 12, 2022) https://jwa.org/thisweek/oct/25/1923/birth-of-beate-sirota-gordon-who-wrote-equality-into-post-war-japanese.

[8] The Only Woman in the Room, A Memoir by Beate Sirota Gordon. Kodansha International, Tokyo-New York-London, First edition 1997. p. 147

[9] Op. cit. p. 159, paragraph 1

[10] Op. cit. p. 159, paragraph 2

[11] Op. cit. p. 88 “After graduation [from Mills College] I transferred to the Office of War Information … My job was to produce broadcasts targeted at the Japanese and designed to simultaneously inform and demoralize – San Francisco’s answer to the broadcasts of Tokyo Rose, the voice of Japanese propaganda for front-line U.S. Troops. The short broadcasts I produced consisted of three minutes of music accompanied by a seven-minute message. I selected the music and wrote the scripts …. I wrote hundreds of shows.”

[12] “My Way” is a song popularized by Frank Sinatra. Its lyrics were written by Paul Anka and set to music based on the French song Comme d’habitude composed in 1967 by Claude François and Jacques Revaux, with lyrics by Claude François and Gilles Thibault. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Way