When I arrived at the Kathak Kendra in July 1967, almost the first question students asked me was “Do you know Shirley and Joe?” I guess they assumed that common dedication by Westerners to such a uniquely Indian art would automatically have caused Raja, Shala and me to meet in America. It turned out that I was only the third Westerner who had studied at the Kendra, and their question was natural, for what did they know about the vastness of the United States, and for that matter, what did I know about India?

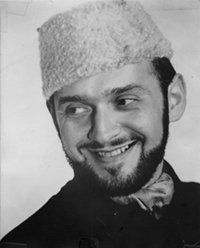

In fact without knowing it, I had met Shirley and Joe in 1965 in Philadelphia, when I attended a performance by Raja & Shala, their professional names. Though I have long ago forgotten the name of the auditorium, I will never forget my brief conversation with Raja. “How long will it take me to learn Kathak?” I asked him after their elegant performance. “A lifetime”, he responded.

In 1975 I became acquainted with Raja and his pithy, acerbic wit. I had met Raja and Shala backstage at Carnegie Hall in 1974, when I acted as Maharaji’s stage and tour manager. Raja subsequently got me involved in an ill-fated off-Broadway play entitled Kali Mother. Despite many over-blown promises about salaries, Raja and I each received one rope on which hung five large brass bells — the total remuneration for hours of rehearsal and several weeks of performances. Five or six ropes of these bells had hung on the stage in a perfunctory attempt at creating the atmosphere of an Indian temple. For years afterward, Raja and I jangled these bells when we visited each other’s apartments, letting out a histrionic, blood-curdling cry “Kalee Mayee kee jayee“, before subsiding into raucous laughter at the memory of our mutual disenchantment.

Following my foray into New York City’s off-Broadway underworld with Raja, I accepted Raja’s offer to teach me his Kathak dance repertoire. He had learned a very bold style of Kathak from my Guru’s uncle, Shambhu Maharaji, and Raja generously shared the recordings, which he and Shala had used during their Kathak performance partnership. During these sessions I learned not to interpret Raja’s sharp wit as cruelty, but rather to meet the challenge of his understated criticisms. “When I asked him how you danced, your Guru said you have a good sense of rhythm. Now I know what he meant”, Raja said, with a suggestive, Groucho Marx-like wiggling of his eyebrows. He expanded by saying outright that my facial expressions were so subtle, that they simply came across as a blank mask. Hard as it was for me to accept, his criticism propelled me into a continuing exploration of the elusive and profound art of Kathak abhinaya – acting through facial expression and body language.

Shala had studied in Bombay with Maharaji’s other uncle, Laachu Maharaji, who choreographed for early Bollywood cinema extravaganzas. She moved to Delhi to study at the Kathak Kendra from Shambhu Maharaji at the same time that Raja studied there. Their dance partnership began in India, and they continued their distinguished career performing Kathak and a cabaret act in North and South America, Canada and the Caribbean. When Shala retired from the stage, she began an on-going process of donating books, props, costumes and other Indian objects to the Kathak Ensemble. Every time I fill my suitcase in preparation for an arts-in-education session in a school, several of Shala’s treasures remind me of the elegant British woman and laughing Lower East Side man who met in India and developed a lifelong friendship based on their mutual love of Indian dance.